Most of the material Mooney gathered for his research on the Cherokee was provided by elders of the tribe who had acquired this knowledge from their elders in the traditional way, passing the information on from generation to generation. Below is Mooney's description of these elders:

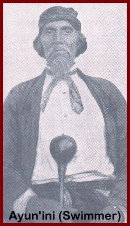

"First and chief in the list of story tellers comes A'yun'ini,

"Swimmer", from whom nearly three fourths of the whole number were

originally obtained, together with nearly as large a proportion of the whole

body of Cherokee material now in possession of the author. The collection could

not have been made without his help, and now that he is gone it can never be

duplicated. Born about 1835, shortly before the Removal, he grew up under the

instruction of masters to be a priest, doctor, and keeper of tradition, so that

he was recognized as an authority throughout the band and by such a competent

outside judge as Colonel Thomas. He served through the war as second sergeant of

the Cherokee Company A, Sixty-ninth North Carolina Confederate Infantry, Thomas

Legion. He was prominent in the local affairs of the band, and no Green-corn

dance, ballplay, or other tribal function was ever considered complete without

his presence and active assistance. A genuine aboriginal antiquarian and

patriot, proud of his people and their ancient system, he took delight in

recording in his native alphabet the songs and sacred formulas of priests and

dancers and the names of medicinal plants and the prescriptions with which they

were compounded, while his mind was a storehouse of Indian tradition. To a happy

descriptive style he added a musical voice for the songs and a peculiar faculty

for imitating the characteristic cry of bird or beast, so that to listen to one

of his recitals was often a pleasure in itself, even to one who understood not a

word of the language. He spoke no English, and to the day of his death clung to

the moccasin and turban, together with the rattle, his badge of authority. He

died in March, 1899, aged about sixty-five, and was buried like a true Cherokee

on the slope of a forest-clad mountain. Peace to his ashes and sorrow for his

going, for with him perished half the tradition of a people.

"Swimmer", from whom nearly three fourths of the whole number were

originally obtained, together with nearly as large a proportion of the whole

body of Cherokee material now in possession of the author. The collection could

not have been made without his help, and now that he is gone it can never be

duplicated. Born about 1835, shortly before the Removal, he grew up under the

instruction of masters to be a priest, doctor, and keeper of tradition, so that

he was recognized as an authority throughout the band and by such a competent

outside judge as Colonel Thomas. He served through the war as second sergeant of

the Cherokee Company A, Sixty-ninth North Carolina Confederate Infantry, Thomas

Legion. He was prominent in the local affairs of the band, and no Green-corn

dance, ballplay, or other tribal function was ever considered complete without

his presence and active assistance. A genuine aboriginal antiquarian and

patriot, proud of his people and their ancient system, he took delight in

recording in his native alphabet the songs and sacred formulas of priests and

dancers and the names of medicinal plants and the prescriptions with which they

were compounded, while his mind was a storehouse of Indian tradition. To a happy

descriptive style he added a musical voice for the songs and a peculiar faculty

for imitating the characteristic cry of bird or beast, so that to listen to one

of his recitals was often a pleasure in itself, even to one who understood not a

word of the language. He spoke no English, and to the day of his death clung to

the moccasin and turban, together with the rattle, his badge of authority. He

died in March, 1899, aged about sixty-five, and was buried like a true Cherokee

on the slope of a forest-clad mountain. Peace to his ashes and sorrow for his

going, for with him perished half the tradition of a people.

Next in order comes the name of Itagu nahi, better known as John Ax,

born about 1800 and now consequently just touching the century mark, being the

oldest man of the band. He has a distinct recollection of the Creek war, at

which time he was about twelve years of age, and was already married and a

father when the lands east of Nantahala were sold by the treaty of 1819.

Although not a professional priest or doctor he was recognized, before age had

dulled his faculties, as an authority upon all relating to tribal custom, and

was an expert in the making of rattles, wands, and other ceremonial

paraphernalia. Of a poetic and imaginative temperament, he cared most for the

wonder stories, of the giant Tsul kalu', of the great Uktena or of the invisible

spirit people, but he had also a keen appreciation of the humorous animal

stories. He speaks no English, and with his erect spare figure and piercing eye

is a fine specimen of the old-time Indian. Notwithstanding his great age he

walked without other assistance than his stick to the last ball game, where he

watched every run with the closest interest, and would have attended the dance

the night before but for the interposition of friends.

Next in order comes the name of Itagu nahi, better known as John Ax,

born about 1800 and now consequently just touching the century mark, being the

oldest man of the band. He has a distinct recollection of the Creek war, at

which time he was about twelve years of age, and was already married and a

father when the lands east of Nantahala were sold by the treaty of 1819.

Although not a professional priest or doctor he was recognized, before age had

dulled his faculties, as an authority upon all relating to tribal custom, and

was an expert in the making of rattles, wands, and other ceremonial

paraphernalia. Of a poetic and imaginative temperament, he cared most for the

wonder stories, of the giant Tsul kalu', of the great Uktena or of the invisible

spirit people, but he had also a keen appreciation of the humorous animal

stories. He speaks no English, and with his erect spare figure and piercing eye

is a fine specimen of the old-time Indian. Notwithstanding his great age he

walked without other assistance than his stick to the last ball game, where he

watched every run with the closest interest, and would have attended the dance

the night before but for the interposition of friends.

Suyeta, "Tbe Chosen One", who preaches regularly as a Baptist minister to an Indian congregation, does not deal much with the Indian supernatural, perhaps through deference to his clerical obligations, but has a good memory and liking for rabbit stories and others of the same class. He served in the Confederate army during the war as fourth sergeant in Company A, of the Sixty-ninth North Carolina, and is now a well preserved man of about sixty-two. He speaks no English, but by an ingenious system of his own has learned to use a concordance for verifying references in his Cherokee bible. He is also a first-class carpenter and mason.

Another principal informant was Ta'gwadihi, "Catawba-killer", of

Cheowa, who died a few years ago, aged about seventy. He was a doctor and made

no claim to special knowledge of myths or ceremonials, but was able to furnish

several valuable stories, besides confirmatory evidence for a large number

obtained from other sources.

Another principal informant was Ta'gwadihi, "Catawba-killer", of

Cheowa, who died a few years ago, aged about seventy. He was a doctor and made

no claim to special knowledge of myths or ceremonials, but was able to furnish

several valuable stories, besides confirmatory evidence for a large number

obtained from other sources.

Besides these may be named, among the East Cherokee, the late

Chief N.J. Smit; Sala'li, mentioned elsewhere, who died about 1895; Tsesa'ni or Jessan, who

also served in the war; Aya' sta, one of the principal conservatives among the

women; and James and David Blythe, younger men of mixed blood, with an English

education, but inheritors of a large share of Indian lore from their father, who

was a recognized leader of ceremony.

Besides these may be named, among the East Cherokee, the late

Chief N.J. Smit; Sala'li, mentioned elsewhere, who died about 1895; Tsesa'ni or Jessan, who

also served in the war; Aya' sta, one of the principal conservatives among the

women; and James and David Blythe, younger men of mixed blood, with an English

education, but inheritors of a large share of Indian lore from their father, who

was a recognized leader of ceremony.

Among informants in the western Cherokee Nation the principal was James D. Wafford, known to the Indians as Tsuskwanun'nawa'ta, "Worn-out-blanket," a mixed-blood speaking and writing both languages, born in the old Cherokee Nation near the site of the present Clarkesville, Georgia, in 1806, and dying when about ninety years of age at his home in the eastern part of the Cherokee Nation, adjoining the Seneca reservation. The name figues prominently in the early history of North Carolina and Georgia. His grandfather, Colonel Wafford, was an officer in the American Revolutionary army, and shortly after the treaty of Hopewell, in 1785, established a colony known as "Wafford's settlement," in upper Georgia, on territory which was afterward found to be within the Indian boundary and was acquired by special treaty purchase in 1804. His name is appended, as witness for the state of Georgia, to the treaty of Holston, in 1794. On his mother's side Mr. Wafford was of mixed Cherokee, Natchez, and white blood, she being a cousin of Sequoyah. He was also remotley connected with Cornelius Dougherty, the first trader established among the Cherokee. In the course of his long life he filled many positions of trust and honor among his people. In his youth he attended the mission school at Valleytown under Reverend Evan Jones, and just before the adoption of the Cherokee alphabet he finished the translation into phonetic Cherokee spelling of a Sunday school speller noted in Pilling's Iroquoin Bibliography. In 1824 he was the census enumerator for that district of the Cherokee Nation embracing upper Hiwassee river, in North Carolina, with Nottely and Toccoa in the adjoining portion of Georgia. His fund of Cherokee geographic informaiton thus acquired was found to be invaluable. He was one of the two commanders of the largest detachment of emigrants at the time of removal, and his name appears as a councilor for the western Nation in the Cherokee Almanac for 1846. When employed by the author at Tahlequah in 1891 his mind was still clear and his memory keen. Being of practical bent, he was concerned chiefly with tribal history, geography, linguistics, and every-day life and custom, on all of which subjects his knowledge was exact and detailed, but there were few myths for which he was not able to furnish confirmatory testimony. Despite his education he was a firm believer in the Nunne'hi, and several of the best legends connected with them were obtained from him. His death takes from the Cherokee one of the last connecting links between the present and the past."

Mooney also made use of a manuscript written by a Cherokee woman named Wahnenauhi, or Lucy Lowery Hoyt Keys, as a source for the stories as well. We feature Wahnenauhi in our Native American Women in History section.

(The photographs on this page are from Bureau of American Ethnology Nineteenth Annual Report)

Books: (The Native History Association is an Amazon Associate. If you buy using one of our Amazon Book links, we get a small percentage of the sale, and we appreciate that support.)